By Dave Tucker April 15, 2010

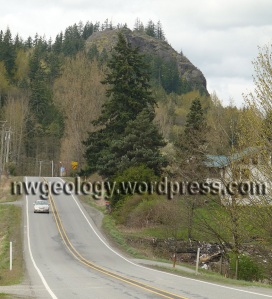

There seem to be as many ‘Bald Mountains’ in these parts as there are bald heads. The high, rounded, isolated 2482 foot (757 m) knob in the Cultus Mountains east of the city of Mount Vernon is an outstandingly curious one. Standing high, steep, and rocky above square miles of clearcuts, this cliffy hill is NOT bald on top. In fact, above the bare rock of the sides, its crown likely holds one of the rare uncut patches of forest for miles and miles, due to inaccessibility. I could be wrong, I haven’t climbed up the dang thing yet, but one look and you’ll think the same. Bald Mountain is resistant seafloor lava, mildly metamorphosed to greenstone- not unlike the quarry visited on the Wells Creek volcanics field trip. The surrounding softer rocks have been entirely eroded away from the metavolcanic greenstone rocks here in the Cultus Mountains. A nearby quarry reveals interesting features in sheared greenschist, and is included in this geologic field trip.

Bald Mountain near the center of a clip from Google Earth. The image is about 2 miles wide. The quarry is near the bottom edge.

Getting there: You may need to walk or ride a mountain bike 2 miles on good graveled roads if the yellow gate is locked- see road log below.

Maps: The relevant topo map is the Stimson Hill USGS 7.5′ topographic sheet. You will likely find Google Earth useful to figure out the roads and to see Bald Mountain in 3-D. There is a geologic map available online and listed in the references, below:

- Drive east on College Way from Mount Vernon; there is an exit from I-5 for this arterial street, which passes Skagit Valley College.

- Intersect with Highway 9 at a roundabout 3.6 miles east of I-5 and set your odometer to zero here. This is known to locals as ‘Big Rock Junction’.

- Turn right (south) on Highway 9; go right under Big Rock (more later) and past Big Lake.

- 6.6 mi (10.6 km) Turn left on the Lake Cavanaugh Rd. 6.6 miles.

- 14.4 miles (23 km) Cross Bear Creek

- 14.7 mi (23.5 km) Turn left on a gravel road. When I visited, the road was unmarked, but I think it is the east end of DNR Road 1000. There is a yellow gate here; if it is locked, park and get out your hiking boots or bicycle. Reset odometer here.

- From the gate the mainline gravel road runs through clearcuts.

- 0.9 miles (1.4 km)-veer gently left at a Y, hopefully signed “DNR 1200”.

- 1.4 mile (2.4 km) If you are on the correct road amongst the maze, reach an intersection at a big quarry.

Geology: The only detailed geology is 1:24,000 field mapping and interpretation by Dragovich and others, 2004. The area is just west of the Sauk River 1:100,000 regional map by Tabor and others (2002). Dragovich and others follow Tabor’s lead and assign these Jurassic low-grade metamorphic rocks to the Helena-Haystack Melange. By that is meant a mix of rock bodies, not necessarily related in age or even provenance (original source), thrown together by intricate, subduction-related faulting. The result is discrete blocks of varied lithologies in close proximity. In the Bald Mountain area hard, resistant greenstone, only slightly metamorphosed, remains as isolated blocks. Hills of resistant rock like this are known to some geologists as ‘knockers’, and that is what we’ll call Bald Mountain. The hypothetical matrix of much softer serpentinite and possible meta-sediments is not exposed on the surface. The numerous greenstone knockers such as Bald stick up as rocky hills, surrounded by thick, and young, glacial deposits. Dragovich and others (2004) report that subsurface serpentinite was reported from some local well logs. Zircons mineral grains in some greenstone map units in the area yielded U-Pb zircon ages of 160 to 170 Ma (Jurassic). For more on the Helena-Haystack, see Tabor and others (2002) and Tabor (1994). As if subduction had not complicated the geology in this area, the strike-slip Devils Mountain Fault Zone has further juxtaposed different rock bodies. This fault system runs east-west in this area, and has brought disparate Chuckanut, Helena-Haystack Melange rocks, and some odd-ball chert, together as slivers.

In the quarry, a white quartz vein is offset by a fault. Lighter green surface is a slickensided fault plane. Yellow hammer for scale.

STOP 1- The greenstone/greenschist quarry is well worth a visit. The features you see may be different from the ones I describe, depending on quarry activity. The rock is blasted and used as road ‘metal’ on the DNR’s road system in these parts. It is fractured greenschist, meaning it was once mafic or intermediate lava (in this case, submarine) that was subducted, subjected to relative high pressure but low temperature, sheared off the subducting sea floor and accreted to the North American plate, uplifted, and now exposed, in part thanks to repeated glacial erosion. Bald Mountain dominates the scene to the north, and we’ll get to it eventually. I spent my time at the quarry looking at rocks and structures in a deep pit just east of the intersection with Road 1200, right along the road running through the quarry. I saw a thick vertical vein of quartz, offset by faulting; shiny serpentinite, which is a metamorphic product of magnesium-rich rocks such as seafloor basalt or mantle peridotite that have been altered by the circulation of hot water; and fault surfaces marked by smooth slickensides.

When you are done with the quarry, continue to the south foot of Bald Mountain.

- from the intersection at the quarry, turn left;

- 1.6 mi (2.6 km) turn right on road 1204 (there was a prominent “M.P. 1.5” sign here);

- 1.9 mi (3.0) km) turn right on unnumbered road heading east. If driving, you may prefer to start walking here. You are directly beneath the south face of Bald Mountain.

- in 0.3 miles, come to a slope of talus blocks fallen from Bald Mountain right above you.

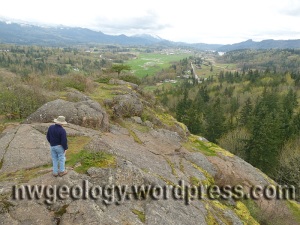

STOP 2- When I was here with Bob, there was fresh snow all over the talus, so we were content to stop at this point. The talus blocks allow examination of the rock of Bald Mountain. I cracked many blocks with my hammer to see past the lichen and weathering; those rocks are really hard, and everything I saw was beautiful, dark, greenstone- no serpentinite and no metamorphic foliation, just massive low-grade metabasalt. I’ll have to return in decent weather to find my way to the summit, and take pics, maybe via the forested north flank. The view out toward Pilchuck Creek, Lake Cavanaugh, and the Stimson Hills to the south must be grand, and perhaps a nice view southeast to Whitehorse Mountain, and the high hills of the Finney Block to the east.

Now, about “Big Rock”. Just east of the Big Rock Junction roundabout, you drove right underneath another of these greenstone knockers, well hidden by the forest. Geology of Big Rock (elevation 525′) is similar to that of Bald Mountain. The hike to the top is short, and gives a fine view southeast up

Nookachamps Creek toward Big Lake, and a not-so-fine view west to a mushrooming subdivision. This rocky little hill was at one time used for rock climbing practice, although I haven’t seen anyone doing that there for many years. To get there:

- Drive 0.2 miles (0.3 km) southeast from the Highway 9 – College Way roundabout. That is Knapp Road. A short 0.1 mile further, pullout on the east side of the road in a wide spot. There is a trail heading into the woods on the other side, perhaps marked with a sign that says ‘15050’. Hike to the eastern base of the final rock knob, then gingerly continue through the mossy slabs a short way to the top.

To get a view of Big Rock, turn off Highway 9 onto Knapp Road, and go far enough to see the knocker rising behind you.

References:

Dragovich, J., Wolfe, M.W., Stanton, B.W., and Norman, D.K., 2004, Geologic map of the Stimson Hill 7.5′ quadrangle, Skagit and Snohomish Counties, Washington: Washington

Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open file report 2004-9.

Tabor, R. W., 1994, Late Mesozoic and possible early Tertiary accretion in western

Washington State—The Helena–Haystack mélange and the Darrington–Devils Mountain

fault zone: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 106, no. 2, p. 217-232, 1 plate.

Tabor, R. W.; Booth, D. B.; Vance, J. A.; Ford, A. B., 2002, Geologic map of the Sauk River

30- by 60-minute quadrangle, Washington: U.S. Geological Survey Geologic

Investigations Series Map I-2592, 2 sheets, scale 1:100,000, with 67 p. text.

Thanks for the info on Bald Mountain, I am a retired builder and over the course of my career I have worked up at Lake Cavinaugh And wondered about the mountain, incidentaly another interesting feature of that area is the floating island on the small lake off of the Lake Cavinaugh road, I dont know much about other than it was used as a log pond once, the island moves from one end to the other depending on wind direction, I have seen it in the middle of the lake in changing weather a couple of times.

Thanks Tom L. Mount Vernon

Tom,

I have camped on that afloating island, it is an old log raft.

DT

Great,

I always thought about mounting a small outboard on it for fun:)

TL

I was out there with my older son with his jeep a couple years ago. We found a road that looped around the backside (northeast side) but were finally stopped by tree fall. We followed the road on foot to where it ended at a creek. Daylight was waning so we had to turn back. We’re going to get to the top of that SOB someday.

I just discovered this blog. A relative lives in Mt. V. and I have gone past Big Rock many times. Today we took a drive and got a far view of Bald. I recall reading about it in Manning’s Footsore books–great fun to read. Thanks for the info about its construction.

Glad you like the blog. I’ll be climbing up Bald in near future, and may have an updated report. Yes, harvey Manning’s Footsore guides are a true NW classic. Should be on everyone’s bookshelf. Dave Tucker

I fly up to the top of Bald mountain once a week for training in my helicopter. The peak is topped by two large exposed boulders and surrounded by 100′ trees. The make-up of the rock on top of the mountain, the exposed flanks, and the base of the mountain are all generally the same composite. If you ever do decide to hike up there, do it in the summertime where there is a small trail on the north side of the mountain. If you feel really adventurous, there is a primitive shelter on the southeast peak cliff face overlooking the valley and quarry below.